Sariska Tiger Reserve is a forest area in the Aravalli Hills, located in Rajasthan, India. Long ago, it had many Bengal tigers living in it. These tigers were an important part of the forest. Sariska got tiger reserve status in 1955. In 1972, India created the Wildlife Protection Act to protect wild animals, including tigers.

Even after protection measures were established, something terrible happened. By 2005, Sariska had zero tigers. All of them were gone. This was a huge shock to India. Questions began to arise, the most important being: can tigers be returned to a landscape where there are none?

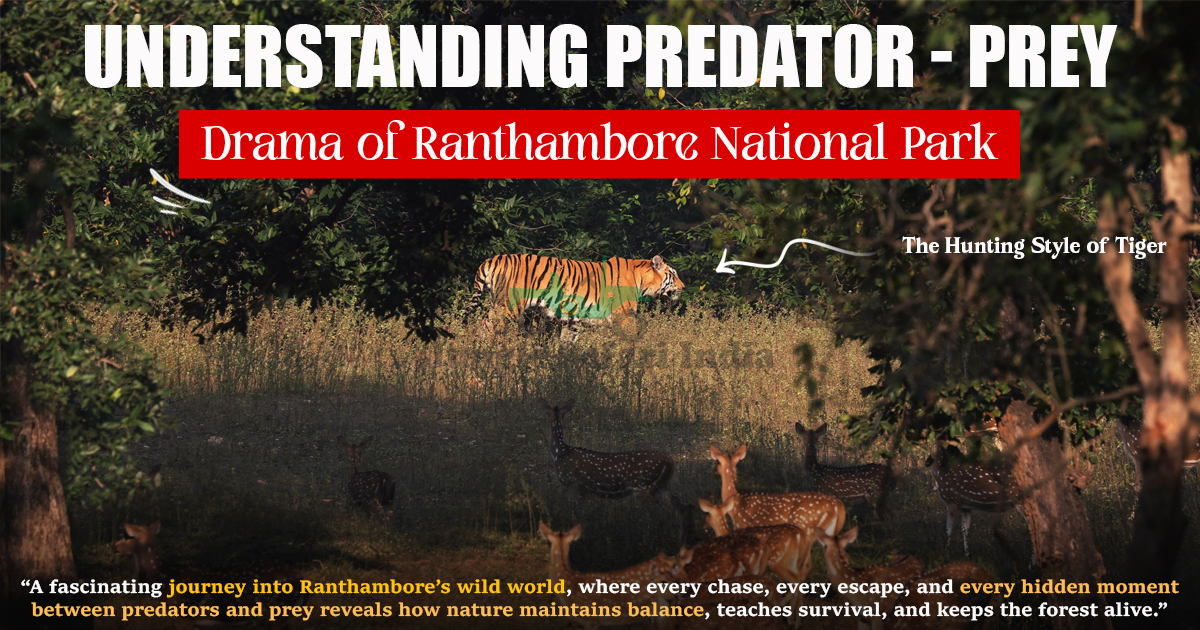

The answer came from another forest called Ranthambore National Park. Ranthambore is also in Rajasthan and has many tigers that can be seen by going on a Ranthambore safari. Because of good protection and care, tigers there were safe and growing in number. The government made a new plan, which played a very important role in helping the Sariska forest become home to tigers again.

The Tiger Problem In Sariska

In the past, Sariska had many tigers. The forest had enough food and water for them. It was a good place for tigers to live. But slowly, the number of tigers started going down.

There were many reasons for this. In earlier times, hunting tigers was a common activity. Kings, foreign visitors, and wealthy people used to hunt tigers for fun and to display power. Later, even after hunting was made illegal, people continued to kill tigers secretly. They did this for money because tiger parts were sold in illegal markets.

Even after 1972, when India passed a strong law to protect animals, poaching (illegal hunting) continued. The law was not always enforced properly. Also, people lived near the forest and entered it often. This made it easy for poachers to kill tigers.

By 2005, no tigers were left in Sariska. Experts visited the park and could not find even one tiger. This news shocked the whole country. It was a big failure in protecting wildlife. The Indian government and wildlife experts knew they had to act fast to fix this.

Help From Ranthambore National Park

Ranthambore National Park is about 200 kilometers away from Sariska. Many people come here for Ranthambore safaris to see the healthy tiger population. This park also faced some problems like human interference and poaching in the past, but strong protection helped the tigers survive.

In 2007 and 2008, the government and forest officials made a special plan. They decided to transfer tigers from Ranthambore to Sariska. This was called tiger relocation or tiger translocation. It was the first time in India that such a thing was done.

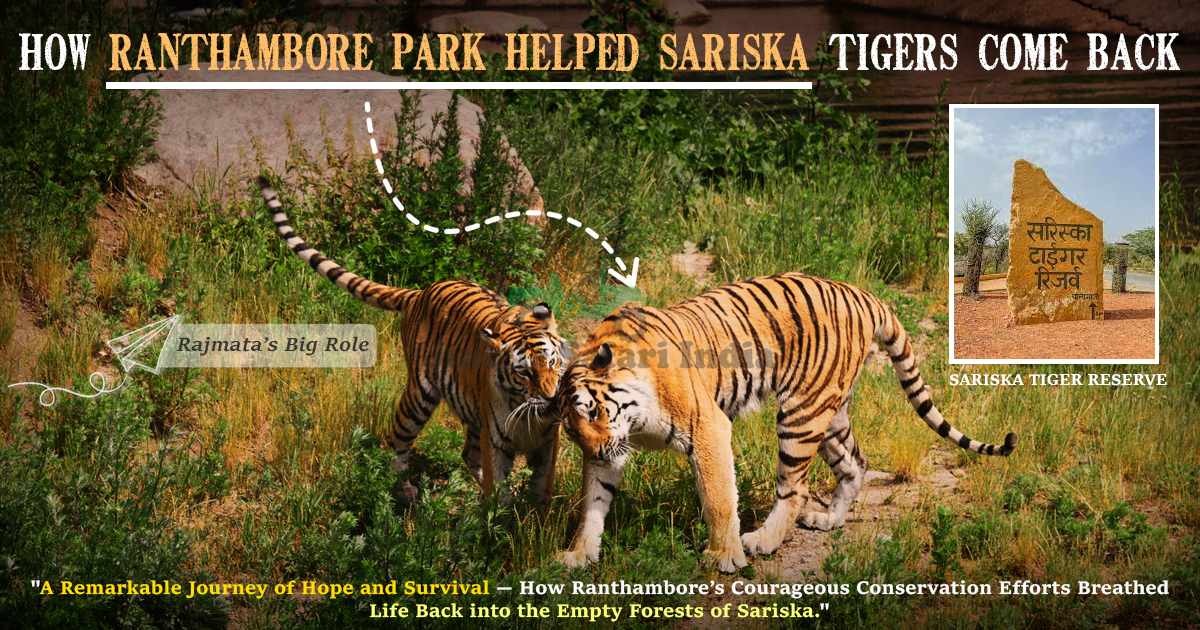

The first tiger moved was a male tiger. He was given the code name ST1. He was moved by helicopter. Just five days later, a young female tiger was also moved. Her name was Rajmata. She later became very important in the story of Sariska.

Moving tigers from one place to another was risky. Tigers are wild animals and do not like change. However, it was necessary because Sariska had no tigers, and time was running out.

Rajmata’s Big Role In Tiger Recovery

After coming to Sariska, Rajmata adjusted well. She started walking around the forest, found a territory, and made it her home. Very soon, she also started giving birth to cubs.

In the next few years, Rajmata gave birth to many tiger cubs. She raised them in the wild. These cubs grew up and became adult tigers. Some of them also had their own cubs. In this way, the number of tigers in Sariska started to grow again.

According to forest officials, more than half of Sariska’s current tiger population is directly related to Rajmata. This means many of the tigers living there today are her children or grandchildren.

Rajmata’s success in having cubs and helping the tiger population grow again is a big reason why Sariska now has tigers. She did not just survive in the new forest – she helped rebuild it.

Because of her big role, the government built a statue of Rajmata in Sariska. She is the first tiger in India to get such an honor. The statue helps people remember her and learn how important she was in bringing tigers back to Sariska.

History Of Hunting In Alwar And Sariska

To understand why tigers disappeared from Sariska, we need to look at the past. Long ago, the area of Alwar, where Sariska is located, was part of a princely state. Kings and nobles ruled here. They hunted wild animals, especially tigers.

Hunting was seen as a sport. It was also used to show power. Foreign guests and important people were often invited for hunting trips. Sometimes rules were made to protect tigresses (female tigers), but they were not always followed.

Some hunters used tricks to catch animals easily. For example, they would mix opium (a drug) in the water that animals drank. This made the animals slow and easy to hunt.

After hunting a tiger, people would take pictures with the dead animal. The tiger’s skin and head were kept in their homes or palaces as decorations. Some of these animal trophies are still kept in old palaces and museums in Alwar today.

Even after India became independent in 1947, hunting continued for some time. People paid money for hunting trips, which harmed the animal population further.

Tiger Numbers Over The Years

Historical records show that Sariska once had many tigers. In the 1800s, there were hundreds of them. But over time, their numbers went down. There were just 15 tigers left in the reserve by 1963. This was already a very low number.

Even though the Wildlife Protection Act was passed in 1972, the poaching of tigers did not stop. Sariska lost all its tigers by 2005 as the number kept going down every year.

Things began to change in 2007 and 2008 when tigers were brought from Ranthambore National Park. Tigers like Rajmata helped restart the tiger population in Sariska. Forest officials kept watch on the tigers using tracking collars and cameras. Food and safe places were provided for tigers to live and raise cubs.

As of the latest report, Sariska now has 48 tigers. This number is still not very high, but it is a big success because the number went from zero to 48 in less than 20 years.

This shows that with strong action, good planning, and care, wild animals like tigers can return to forests where they had disappeared.